Source: AGBU, December 22, 2020

Given its century-old history of advocating for the human rights and dignity of the Armenian people, the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) has long recognized the importance of supporting all victims of ethnic cleansing, genocide and other crimes against humanity around the world. That is why it continues to observe December 9th—the United Nations International Day of Commemoration and Dignity of the Victims of the Crime of Genocide and the Prevention of this Crime–with inclusive discussions of an international scope, each year focusing on a different theme related to this vast, multi-dimensional subject.

This year, one of two virtual events were organized by the AGBU Central Office in New York in partnership with the Promise Institute for Human Rights, operating out of California.

Video of the online discussion (1 hr 10 min) – here.

Truth and Accountability: Ethnic Cleansing in the Modern Age

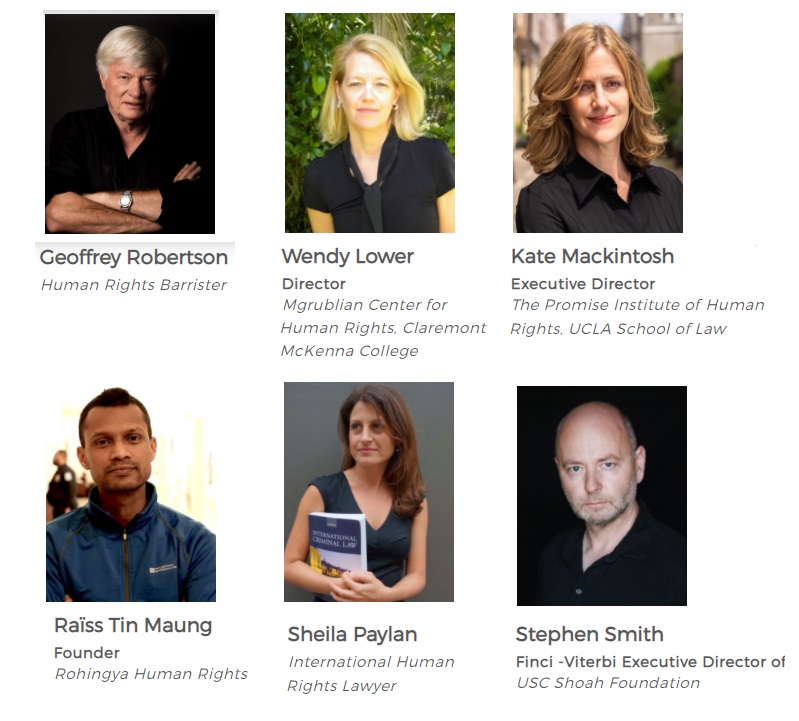

On December 10th, an open conversation hosted by AGBU and the Promise Institute for Human Rights featured

- international war crimes barrister Geoffrey Robertson QC;

- esteemed human rights lawyer Sheila Paylan;

- Raees Tin Maung of the Rohingya Human Rights Network of Canada;

- Stephen Smith, the executive director of the USC Shoah Foundation,

- Kate Mackintosh, the executive director of the Promise Institute of Human Rights at the UCLA School of Law;

- and moderator Wendy Lower, director of Mgrublian Center for Human Rights at Claremont McKenna College.

The thrust of the discussion centered on raising awareness and holding perpetrators accountable for ongoing atrocities.

In his opening remarks, Robertson asserted: “The denial of genocide is a way of perpetrating and perpetuating genocide, adding that “the wickedness of the Ottoman Empire in 1915 was seen over the sky and over the Artsakh mountains in 2020.” Emphasizing the necessity of finding ways to prevent genocide, ethnic cleansing, and war crimes, he emphatically declared, “We have international laws to prevent genocide, but we don’t have the will to enforce those laws.”

Picking up on the recent war in Nagorno-Karabakh, Lower stated: “We feel the echoes of history in the Nagorno-Karabakh region. One hundred years on, the echoes of that history are with us at this very moment.” She added that the definition and weight behind the legal term Genocide have often prevented economic and legal action, a conclusion shared by all the panelists.

Mackintosh remarked, “If we think about some of the mass atrocities that have taken place last century, they have not met the legal definition of genocide. But no one would deny that those are terrible, terrible things that we want to prevent.”

Focusing on taking action rather than letting politics interfere with the actionable change, Smith said, “What’s important is establishing: what’s the intent; what’s the endgame; and what are we going to do to mitigate that and highlight that. The definitional issue gets us a little entrapped because it politicizes it.”

All speakers agreed that the collection of eyewitness reports is an essential tool that victims and activists can use to document cases of injustice. Smith, a specialist in the collection of testimonies of victims of mass atrocities, explained. “For those who are experiencing unfolding mass violence, what they need to know is that people are hearing them, that they do not feel abandoned. Make it clear that we really do care for each other. That’s half of the battle.”

Paylan posited that more often than not, seeking legal justice is a complex process. “When it comes to lending humanitarian aid, it tends to be easy to garner support for it,” she noted. “When it comes to seeking accountability for crimes, it’s a much more difficult process.” She also pointed out that in the case of Artsakh, social media proved key in collecting evidence. “All the hatred that is spewed by the highest-ranking officials of Azerbaijan on Twitter and Facebook – this is evidence. If it’s not collected and preserved right away, it will disappear.” She advocated for the centralization of this documentation as a priority for open-source investigators.

The conference concluded with panelists suggesting optimum ways to prevent or prosecute human rights crimes, such as holding inter-ethnic and inter-religious discussions. Maung made an astute observation: “The people who are doing the most effective and noble work are people in inter-ethnic and inter-religion bridging. It is crucial that we collaborate and show solidarity. Yesterday it was them, today it was us, and tomorrow it could be someone else.”

One thought on “Truth and Accountability: Ethnic Cleansing in the Modern Age in Artsakh”